From: Peter Behr, E&E reporter, published:

Ohio’s Utica Shale is starting to give up its secrets, slowly and stubbornly.The first results from a handful of initial wells paint a mixed picture of the potential oil and gas production from the expansive Utica play that has inspired predictions of a hydrocarbon El Dorado in Ohio from politicians, prospectors and promoters alike.The output of “wet” gas — combining dry heating gas and gas liquids — continues to excite the energy companies that have staked claims in a narrow band on the state’s eastern border.But the search for more lucrative shale oil farther west in the state’s center has disappointed and frustrated the few attempts to find it so far, according to company reports and comments at analysts’ conferences this month.”There are people who have a vested interest in the play. They still have high hopes that it will be one of the top four in the country,” said Fadel Gheit, a managing director and senior energy analyst with Oppenheimer & Co. “Those who don’t have a big stake are watering it down. They are saying it is not as good as Bakken or the Permian Basin. So the jury is still out.”

Ohio’s Utica Shale is starting to give up its secrets, slowly and stubbornly.The first results from a handful of initial wells paint a mixed picture of the potential oil and gas production from the expansive Utica play that has inspired predictions of a hydrocarbon El Dorado in Ohio from politicians, prospectors and promoters alike.The output of “wet” gas — combining dry heating gas and gas liquids — continues to excite the energy companies that have staked claims in a narrow band on the state’s eastern border.But the search for more lucrative shale oil farther west in the state’s center has disappointed and frustrated the few attempts to find it so far, according to company reports and comments at analysts’ conferences this month.”There are people who have a vested interest in the play. They still have high hopes that it will be one of the top four in the country,” said Fadel Gheit, a managing director and senior energy analyst with Oppenheimer & Co. “Those who don’t have a big stake are watering it down. They are saying it is not as good as Bakken or the Permian Basin. So the jury is still out.”

One of the bookends for these disparate judgments is Chesapeake Energy’s Buell well in Harrison County southeast of Canton. The Buell well started production a year ago, with a combined daily production of oil, dry and wet gas equivalent to 3,000 barrels of oil. About half of the production was liquids.

The find fired the enthusiasm of Chesapeake CEO Aubrey McClendon, whose company has 1.3 million net acres of potential drilling sites in Ohio under lease. McClendon’s widely quoted assessment then was that oil and gas production in the Utica play could total $500 billion over time — “the biggest thing economically to hit Ohio since maybe the plow.”

The Buell well is currently producing 1,040 barrels of oil equivalent per day, and other Chesapeake wells in Harrison County and adjacent Carroll County are also delivering good results, the company reported this month. “We love what we see on the wet gas side,” McClendon said. So do officials at other companies, including Gulfport Energy and Antero Resources.

Gulfport said its Wagner well in Harrison County produced 17.1 million cubic feet of natural gas per day (equal in heat value to 2,850 barrels of oil), plus 432 barrels of oil and 1,881 barrels of natural gas liquids. “It has great deliverability,” said Tom Martel, chief geologist with Corridor Resources in Nova Scotia, who authored a paper on the Utica and comparable Canadian shale areas. “There is no question the production out of these [wet gas] wells is stellar.”

By contrast, shallower traditional Ohio wells that do not utilize hydraulic fracturing typically deliver 50,000 cubic feet of gas per day and less than 1 barrel of oil, said Gulfport, which intends to drill 200 wells in that area in the next four years.

The other bookend is the announcement by Devon Energy Co. that results from two wells drilled in Medina and Ashland counties west of Akron “were not encouraging,” without providing details. These projects were testing the western edges of oil-bearing shale in those counties, and given the premium price that oil receives over gas, the reports of failure undermined the rosiest Utica scenarios, at least for now, some analysts say.

The Devon wells “were so far west [that] it wasn’t a complete surprise that it didn’t work,” said Biju Perincheril, an energy analyst with Jefferies & Co. Inc. Devon says it will keep drilling.

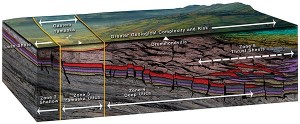

Geologists explain that the Utica Shale tilts from shallower depths in central Ohio to deeper ranges along the Ohio-Pennsylvania border, where some wells have penetrated 2 miles or more below ground. The current sweet spot on the state’s eastern fringe has the right combination of age, depth and pressure to produce wet gas. The less mature oil-bearing sections mid-state may not have enough internal pressure to deliver oil effectively and profitably.

Figuring out the ‘oil window’

“Probably the biggest question is: How does the oil window work? We’re still waiting on data,” Perincheril said.

“It’s not that they’re abandoning the west, but the commentary has slowed down as they’re tried to figure it out,” said Ronald Mills, an analyst with Johnson Rice & Co. It is too soon to judge Utica’s oil potential, Chesapeake’s McClendon told analysts this month.

The first caveats about the potential Utica Shale output came from the state’s then-top geologist, Larry Wickstrom. In a 2011 report, Wickstrom and colleagues had assessed the Utica and linked the Point Pleasant Shale play at 17,000 square miles, nearly equal to the size of the Eagle Ford play in southeastern Texas, a top hot spot for unconventional oil and gas exploration.

Then, in March, Wickstrom surprised industry officials with an updated assessment that narrowed the play’s footprint considerably. Wickstrom’s PowerPoint presentation before the Ohio Oil and Gas Association on March 16 listed parts of a dozen Ohio counties with “excellent” or “very good” prospects, based on an analysis of rock core samples. All or parts of two dozen other counties in the play were rated “fair” or “poor.” Much of the “oily” part of the Utica Shale was low-rated.

Wickstrom’s presentation emphasized that the assessment was very preliminary and incomplete. There could be good finds within a “poor” region and failed wells in a “good” one. Only more drilling could answer the question, he said.

Industry and officials did not welcome the downbeat assessment. Companies hoping to sell acreage would not want that news. Nor would landowners hoping to sign leases and earn royalties. (Encore Energy Inc. in Kentucky, for example, has announced its intention to sell up to 175,000 leased acres in five southeast Ohio counties — two of which lie outside the revised Utica boundaries in the new Wickstrom map.)

Fatefully for him, Wickstrom also apparently surprised his bosses at Ohio’s Department of Natural Resources, which both regulates and promotes shale drilling. The 29-year veteran was removed May 9 as chief of the department’s Division of Geological Survey, after five years in that post. He has since retired.

His evaluation on April 12, obtained by reporter Russ Zimmer of the Media Network of Central Ohio under the state’s public records law, complained among other things that Wickstrom developed the new map “changing public perception about the shale play” but did not provide it to the division administrator until four days later.

“Outside scientific reviews of this new map question its accuracy and numerous landowners across southern Ohio are concerned about how the map may be used to devalue potential future mineral rights leasing,” the evaluation said. Those outside reviews had not been released as of last week.

Attempts to contact Wickstrom were not successful. Ohio DNR spokeswoman Heidi Hetzel-Evans said, “chiefs routinely serve at the pleasure of the director, and we don’t generally discuss personnel issues like that.” Wickstrom’s former colleagues at the Geological Survey would not discuss his situation.

“Our rig count continues to increase, and we see new companies continuing to come into Ohio,” Hetzel-Evans added. Any assessments now, however, are absolutely conjectural. “We are two to three years away from a good idea of what production we can expect out of the Utica Shale.”

Utica’s mysteries

This spring, Wickstrom and colleagues estimated that the Utica Shale’s potentially recoverable reserves could range from a low of 3.75 trillion cubic feet of gas and 1.31 billion barrels of oil to a high of 15.7 trillion cubic feet gas and 5.5 billion barrels of oil. The exploration is still too new to permit closer assessments, experts agree.

“In general, the Utica has been less intensively drilled over the years because it’s so deep,” said John Conrad, president of the gas-drilling consulting firm Conrad Geoscience Corp. in Poughkeepsie, N.Y. “We have a much better understanding of the Marcellus Shale,” which is several thousand feet shallower, he said.

Even the potential of the wet gas, Utica’s most promising product, is obscured for several reasons.

Ohio reports shale production annually — the next data are not due until next spring. On the production side, drillers have begun resealing wells for two months immediately after fracking to allow the fracking water to be absorbed into rock pores, opening an easier path for gas and oil production, notes Mills. “That has pushed the results out and left more of a question mark about the play than during the original excitement last year,” he said.

And the wet gas production won’t reach full capacity for another year or two, when new or reconfigured pipelines and processing units are in place to export gas liquids — ethane, propane and butane.

There are also intrinsic questions about the ultimate amount of shale oil and gas that can economically be recovered in the next decades, says the federal Energy Information Administration.

The current EIA annual outlook says that U.S. shale gas production could range from as low as 10 trillion cubic feet (tcf) a year in 2035 to twice that amount, depending on critical, unpredictable variables of prices, regulation, demand and technology.

EIA’s 2010 annual outlook using 2008 data estimated the technically recoverable shale reserves in Appalachia at 59 tcf, excluding economic factors. The next year, the boom in Marcellus exploration caused EIA to raise the estimate to 441 tcf, against the current annual U.S. gas consumption of about 26 tcf. Then, more constrained drilling results from representative Marcellus wells caused EIA to drop the estimate to 187 tcf this year.

“Many of these plays have only been drilled in what one would call sweet spots, so it’s not clear what other parts of the formation are able to produce,” said EIA analyst Philip Budzik in a June interview. “Most of these wells have had relatively short production times, so we don’t know what their long-term production rates are,” he said.

Another part of the riddle: shale gas and oil wells typically behaving very differently than conventional wells with production that ramps up — and then drops off — much more quickly.

“If you look at the [shale production] curve, it shoots up first. It comes down hard. Then there is the long tail,” lasting 20 years or more, Gheit said. The financing of shale oil and gas creates a bias for extracting the bulk of the production quickly, but then wells will continue to provide smaller rewards for a long time. “It’s like sitting on a toll booth,” Gheit said.

“But some shales drop off precipitously, and others hold up quite a bit longer,” Martel said. The difference can be critical for the project’s economics. “These are subtleties you don’t know until you produce the wells for a period of time.”

All of this leaves questions buzzing around the Utica play.

“So far, it has not lived up to expectations,” Gheit said. But time will tell.

Source of the article: http://www.eenews.net/energywire/2012/08/20/1

Keep working ,terrific job!

I simply wanted to post a simple comment to thank you for these stunning concepts you are sharing at this website. My long internet look up has now been honored with wonderful know-how to go over with my pals. I would repeat that most of us readers are really fortunate to dwell in a wonderful site with very many wonderful individuals with beneficial suggestions. I feel very privileged to have seen your web site and look forward to plenty of more amazing minutes reading here. Thanks again for everything.

Great write-up, I抦 normal visitor of one抯 website, maintain up the excellent operate, and It’s going to be a regular visitor for a long time.

Hi would you mind sharing which blog platform you’re using? I’m going to start my own blog in the near future but I’m having a hard time selecting between BlogEngine/Wordpress/B2evolution and Drupal. The reason I ask is because your layout seems different then most blogs and I’m looking for something completely unique. P.S Sorry for getting off-topic but I had to ask!

I know this if off topic but I’m looking into starting my own weblog and was curious what all is needed to get set up? I’m assuming having a blog like yours would cost a pretty penny? I’m not very web savvy so I’m not 100 positive. Any tips or advice would be greatly appreciated. Cheers

Wonderful work! This is the type of info that should be shared around the web. Shame on Google for not positioning this post higher! Come on over and visit my site . Thanks =)

I have realized that over the course of creating a relationship with real estate homeowners, you’ll be able to come to understand that, in most real estate financial transaction, a percentage is paid. In the end, FSBO sellers will not “save” the commission rate. Rather, they fight to earn the commission by doing a good agent’s work. In the process, they shell out their money along with time to complete, as best they could, the duties of an broker. Those jobs include revealing the home by marketing, showing the home to buyers, building a sense of buyer urgency in order to trigger an offer, making arrangement for home inspections, managing qualification checks with the bank, supervising maintenance, and aiding the closing.

Yet another issue is that video games are generally serious as the name indicated with the main focus on learning rather than amusement. Although, there’s an entertainment facet to keep your kids engaged, just about every game is frequently designed to work with a specific group of skills or course, such as mathematics or scientific research. Thanks for your publication.

Thanks for the suggestions shared on your blog. Another thing I would like to convey is that weight reduction is not information about going on a fad diet and trying to shed as much weight as possible in a couple of weeks. The most effective way to burn fat is by acquiring it slowly and using some basic guidelines which can make it easier to make the most from a attempt to lose fat. You may be aware and already be following many of these tips, nonetheless reinforcing understanding never affects.

This design is incredible! You certainly know how to keep a reader amused. Between your wit and your videos, I was almost moved to start my own blog (well, almost…HaHa!) Fantastic job. I really enjoyed what you had to say, and more than that, how you presented it. Too cool!

Spot on with this write-up, I actually assume this web site needs way more consideration. I抣l in all probability be once more to read far more, thanks for that info.

Hello there! Do you know if they make any plugins to assist with Search Engine Optimization? I’m trying to get my blog to rank for some targeted keywords but I’m not seeing very good success. If you know of any please share. Many thanks!

Hello there, I found your website via Google while looking for a related topic, your website came up, it looks great. I have bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.

Hi there, simply become alert to your weblog via Google, and located that it is really informative. I am gonna be careful for brussels. I will appreciate should you continue this in future. A lot of folks will probably be benefited from your writing. Cheers!

It抯 actually a great and helpful piece of information. I抦 satisfied that you shared this helpful info with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thank you for sharing.

There are some fascinating time limits in this article but I don抰 know if I see all of them middle to heart. There’s some validity but I’ll take hold opinion until I look into it further. Good article , thanks and we would like more! Added to FeedBurner as well

I see You’re in reality a good webmaster. The site loading

speed is incredible. It sort of feels that you

are doing any unique trick. Moreover, the contents

are masterwork. you’ve performed a magnificent

task in this topic! Similar here: <a href="[Link deleted]sklep and also here: <a href="[Link deleted]zakupy

Hello There. I found your blog using msn. This is a really well written article. I will be sure to bookmark it and come back to read more of your useful info. Thanks for the post. I抣l definitely return.

I have taken notice that in unwanted cameras, unique devices help to maintain focus automatically. Those kind of sensors associated with some surveillance cameras change in in the area of contrast, while others utilize a beam involving infra-red (IR) light, specially in low light. Higher spec cameras occasionally use a mixture of both systems and will often have Face Priority AF where the dslr camera can ‘See’ some sort of face while keeping focused only on that. Thanks for sharing your opinions on this weblog.

Wow that was odd. I just wrote an very long comment but after I clicked submit my comment didn’t appear. Grrrr… well I’m not writing all that over again. Anyways, just wanted to say wonderful blog!

Well I definitely liked reading it. This subject offered by you is very effective for proper planning.

Hi there I am so glad I found your web site, I really found you by mistake, while I was looking on Bing for something else, Regardless I am here now and would just like to say kudos for a marvelous post and a all round interesting blog (I also love the theme/design), I don抰 have time to read through it all at the minute but I have saved it and also added in your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read more, Please do keep up the excellent job.

Hello There. I found your blog using msn. This is a really well written article. I抣l make sure to bookmark it and return to read more of your useful information. Thanks for the post. I抣l certainly return.

I will right away grab your rss as I can’t find your email subscription link or newsletter service. Do you’ve any? Kindly let me know in order that I could subscribe. Thanks.

Hi, Neat post. There’s a problem with your website in internet explorer, would check this?IE still is the market leader and a large portion of people will miss your great writing due to this problem.

Hello! Do you know if they make any plugins to help with SEO?

I’m trying to get my website to rank for some targeted keywords

but I’m not seeing very good success. If you know of any please

share. Thanks! You can read similar article here: <a href="[Link deleted]List